The post How many species are in the deep sea? first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>

After Pliny’s monstrosity, many centuries went by before this question was really tackled again. In 1815, Edward Forbes took a ride aboard the HMS Beacon, where he dredged the bottom at depths from 1-1,380 feet (0 – 420 m). Just so you know, the average depth of the ocean is about 12,000 feet (4,000 m). So, when I say he was barely scratching the surface, I’m not really exaggerating. But nevertheless, he dredged the depths that he did and found that the deeper he dredged at, the less things he found. So naturally, he thought, there must be a “zero point” at which no animals live. He wildly extrapolated his data and determined that below 1,800 feet (600 m) there exist no animals, and he called this the “azoic zone.” So, Forbes’ answer to how many species in the deep sea was a big fat “not many.”

Luckily this “azoic zone” nonsense only lasted about 50 years. In 1869, Charles Wyville Thomson and the rest of the crew onboard the HMS Porcupine pulled up animals from 14,610 feet (4,450 m) deep in the waters south of Ireland. These results were later confirmed by the Challenger expedition which found animals at all depths, all over the globe. This undeniably proved there was life at all depth of the oceans- but the question still remained. How many species in the deep sea?

Fast forward to 1992. Frederick Grassle and Nancy Maciolek conduct a massive (for the time) survey of the tiny animals that live in the sediments in the deep sea. These are not the cute crawlies that live on top of the mud that had been previously sampled with dredges. These are the small animals that live their lives between the grains of dirt at the bottom of the ocean. Of the 798 species that they found, over half were new to science! Pliny’s head would explode if he heard that more than double the total animals he thought existed in the whole ocean were found just in the mud.

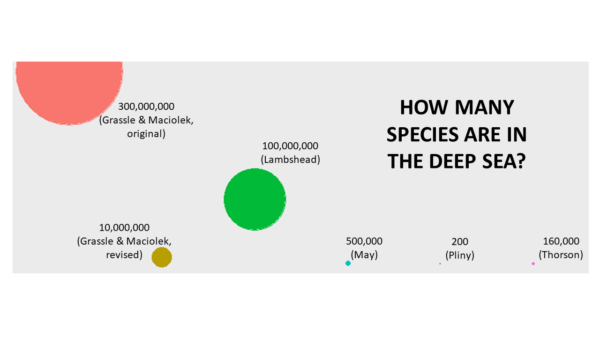

Grassle and Maciolek did some impressive math and ended up calculating that they were finding one new species per square kilometer they sampled. Let’s break that down. One square kilometer is equal to a little more than one-third of a square mile. So, they are basically finding three new species in each one-mile-square block of mud they are sampling. This means if they were to sample an area the size of New York City, they would find around 782 new species, and if they were to sample an area the size of London, they would find about 1,572 new species. These new species add up fast – you see, there are 300,000,000 square kilometers (115,830,647 square miles – almost 30 Europes or 431 Texases) of mud deeper than 1000 m in the ocean. The end result of all this is a conclusion of 300,000,000 species living in the mud at the bottom of the deep ocean. This is not counting swimming things! That’s a heck of a larger estimate than the 176 species estimate of centuries ago.

.It turns out that this calculation of Grassle and Maciolek was probably a bit of an overestimation. They realized that much of the ocean is oligotrophic, or not very nutrient-rich and therefore not very productive. This would mean that in many areas of the ocean, the rate of new species added per square kilometer is probably much less than what they found in their sampling area. So, they ended up conservatively estimating the true number at more like 10,000,000 species in the mud. This is still a huge amount of diversity in the deep sea.

Grassle and Maciolek’s 10 million species hypothesis sparked quite the controversy, with biologists from many sub-disciplines quickly arguing for or against the high number. Isopod biologists Poore and Wilson said they had seen even more diversity just among isopods in their samples than the average number of species per 100 samples that Grassle and Maciolek had used in their calculations. This, they argued, must mean there are even more than 10 million species! In 1971, though, Thorson argued that there were only 160,000 species in the oceans across all depths- so far less than 10 million could be in the deep sea. In 1992, May argued that only 500,000 species would be possible in the deep sea. Lambshead in 1993 reminded everyone that there are a boatload of nematode worms and other animals (collectively called meiofauna) that live in the mud that were too small to be sampled by the gear Grassle and Maciolek used. This, Lambshead argued, could mean a total of 100,000,000 marine species. Consensus just could not be reached.

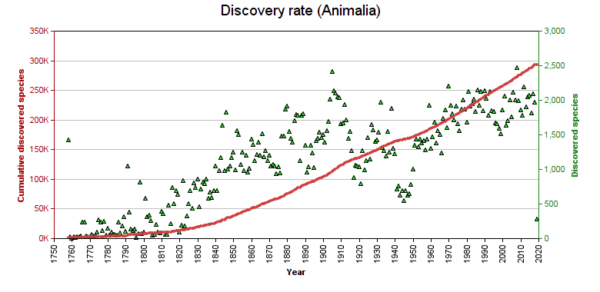

Here’s the problem, though. It is a hard question to answer. Each person who has attempted to answer this question was doing the best with the data that they had at the time (except Pliny- that guy was just an idiot okay). However, species diversity and especially how many species you discover in each new deep-sea “block” can vary considerably at different depths, regions, and oceans. Grassle and Maciolek’s encoutering 3 new species per block was based on data from the North Atlantic. Does 3 new species “rule” also apply to other parts of the Atlantic or to the Pacific? So without massive amounts of data, it is likely we will be kept guessing for a few more years to come. So, I can’t tell you exactly how many species are in the deep sea, but I can tell you that we currently have 409,543 named species in the ocean (World Register of Marine Species, accessed 03/18/2019). The best part is that we are getting better and better at discovering new species, and hopefully in years to come we will be much better equipped to answer this question realistically.

Cover photo credit to Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI).

The post How many species are in the deep sea? first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>The post Deep Sea 101: Early Paradigms and Exploration first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>While the Census of Marine Life may be the most recent call to survey the ocean, deep-sea exploration has a rich, paradigm-shifting history. It has all the makings of a Hollywood blockbuster: colorful characters, high seas action, the drama of antagonistic actions between “men of honor”, you name it! Probably has a bit of romance in there too, but that tends to get left out of the scientific literature. Examining the history of deep-sea exploration is an excellent case study in how technological advances continue to yield new insights and increase our ability to ask better questions. This section of Deep Sea 101 will be composed of 4 parts.

Nearly 2400 years ago Socrates (via Plato) posited of the deep sea:

“… everything is corroded by the brine, and there is no vegetation worth mentioning, and scarcely any degree of perfect formation, but only caverns and sand and measureless mud, and tracts of slime wherever there is earth as well, and nothing is in the worthy to be judged beautiful by our standards.”

Such a damning indictment from such a classical thinker indeed! Curiously, the Greeks and other civilizations during this time were in no position to make such bold statements having an inability to visit and sample past a mere tens of a meters.

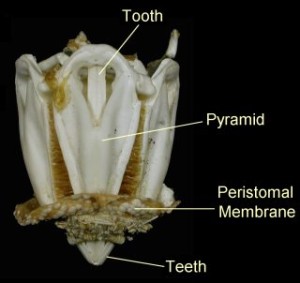

It was not until Aristotle we could really call anyone a marine biologist. He dedicated much of his life to describing the life on the Aegean coasts, describing 180 marine species nearly 1700 years before Linneaus. Aristotle was the first person to study form, function, ecology and behavior and developed a classification system based on multiple traits. He is perhaps most famous for describing the mouth parts of sea urchins, which is named in his honor (called Aristotle’s Lantern, at right).

But his enthusiasm for the ocean did not catch on in the ancient period and an attitude of complacency persisted all the way towards the Victorian Era when deep-sea exploration really took off, chiefly out of economic and imperial interests. Echoing the contented ignorance of the time, or perhaps a fear of the unknown, noted historian Pliny the Elder wrote in 40 AD:

“By Hercules, in the sea and in the ocean, vast as it is, there exists nothing that is unknown to us, and a truly marvelous fact, it is with those things that that has concealed in the deep that we are best acquainted!”

It took until the 17th century, during the tail end of the Renaissance, for these unfounded assertions to be even questioned, and by none other than Robert Hooke who stated:

“Animals and Vegetables cannot be rationally supposed to live and grow under so great a Pressure, so great a Cold, and at so great a Distance from the Air, as many Parts at the Bottom of very deep Seas are liable and subject to…

We have had instances enough of the Fallaciousness of such immature and hasty Conclusions…” (emphasis mine)

What Hooke has done was twofold. He first provided a set of testable hypotheses for absence of life in the deep sea disguised as common sense. Then, he made a statement hinting that perhaps we ought to actually test this because if past experience shows, common sense might not always be correct.

For the next 100-200 years the deep sea was considered lifeless based on 4 criteria: temperature, light, pressure and stagnancy of the environment (i.e. it was all uniform). The first three of these criteria were well-reasoned, though no one knew what the true depths of the deep sea were. But it was well-known that light was refracted by water and the visible spectrum gets filtered out, the deeper you go the more pressure an organism must bear – this is easily calculated estimating forces, and without the energy from the sun’s rays warming the deep waters it could be reasoned that it must be cold down there. In fact, some early scientists thought the bottom of the sea must be ice.

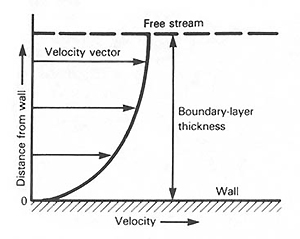

The last criteria of stagnancy is an interesting one that I am not entirely sure how it came about since they had no direct knowledge of deep-sea life until the mid-1800s. It may have been derived from calculation of the current speeds. Surface currents are wind-driven and any given body of water tends to be stratified, or composed of different layers. The top layer of the water moves at a given speed but experiences drag from rubbing against the layer of water below it. This causes the lower layer to move with the upper layer but at a slower speed because there is energy loss from friction against the seafloor (see figure at right). Because of this, water currents near the seafloor are typically much slower than surface currents. Therefore one can posit that at some depth water speed eventually just stops. This has important implications because animals down there would need fresh, constant input of dissolved nutrients (nitrogen, oxygen, etc.). Stop the flow, there’s no grow!

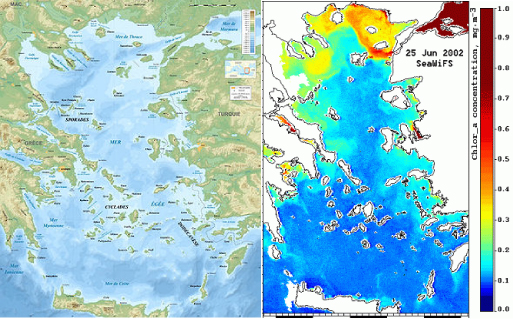

During the golden age of deep-sea exploration in the 1800s the Azoic Hypothesis of the deep-sea was largely championed by Edward Forbes and was based on his observations in the Aegean Sea, between Greece and modern-day Turkey (map below). I’ll refer to the Azoic Hypothesis as tied specifically to Forbes, but recognize that it had much earlier roots. Forbes was merely the first to study it scientifically. As I’ll go on to explain though, the Azoic Hypothesis was largely the result of common sense thinking, an unfortunate study area, inadequate sampling gear and ignoring previous results.

Though not known at the time, the Aegean Sea was a poor choice for a study site. First of all, it is not very deep and we now know it is not a very productive area away from coastal areas. The map above (at right) shows the concentration of chlorophyll – the pigment used by phytoplankton to capture solar energy to use in photosynthesis – in the Aegean Sea based on satellite measurements. Green to red signify higher concentrations of phytoplankton, and hence higher amounts of surface primary production. Blue is low productivity and you’ll notice that in the center of the Aegean Sea where the deep water is it’s mostly blue, or unproductive. Oligotrophic waters (meaning with few nutrients) are defined as containing less that 80 grams of carbon per square meter. The central Aegean Sea has about 30 grams of carbon per square meter. With very few plankton at the surface, there is very little food that falls down to support the denizens of the deep.

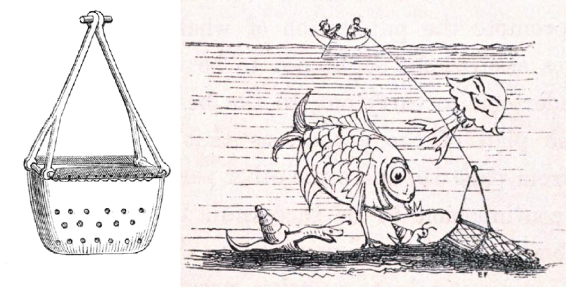

Had Forbes actually been in a productive area he still might not have found much life in the deep because he was using a dredge that was modified from ones used by oystermen. It was inadequately designed to sample the muddy deep seafloor. The mouth of the dredge was narrow and the bag was small. Note the design of the canvas bag (below, at right), there are vents only in middle of the sides. The dredge would immediately fill up with mud and thereafter become a wrecking ball let loose upon the seafloor until it was brought up. Curiously though, and deceptively, Forbes made an illustration of sea creatures all-too-happy to enter into his dredge for his book Natural History of the European Seas (his initials are under the dredge). But the difference between the dredge he used versus this idealized dredge that he illustrated is actually quite important. The illustrated dredge would have been ideal to use since it has a wide mouth and plenty of vents to discharge mud.

Throughout his sampling, he failed to document life in the deep, but did document very thoroughly patterns of animal abundance with depth. In general, the deeper his dredge dove the fewer organisms he found. He wrote in 1859, the same year as Darwin published On the Origin of Species:

Throughout his sampling, he failed to document life in the deep, but did document very thoroughly patterns of animal abundance with depth. In general, the deeper his dredge dove the fewer organisms he found. He wrote in 1859, the same year as Darwin published On the Origin of Species:

“As we descend deeper and deeper in this region, its inhabitants become more and more modified, and fewer and fewer, indicating our approach towards an abyss where life is either extinguished, or exhibits but a few sparks to mark its lingering presence.”

By means of extrapolation he asserted that life ceased to exist beyond 550 meters. Which probably seemed pretty reasonable to Forbes’ contemporaries. Forbes had went out to sea, carried out an extensive sampling program and had based his conclusions on data. In hindsight we can say that Edward Forbes was ill-prepared to adequately sample the deep sea and had a poor choice of study area, but was his extrapolation just the result of bad luck, or is there more to the story?

Find out in the next installment of Deep Sea 101 as we continue to examine the early evidence for life in the depths during Forbes’ time and enter whom I refer to as the father of modern oceanography, Sir Wyville Thomson!

The post Deep Sea 101: Early Paradigms and Exploration first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>The post Pouring Oil on ‘Troubled Waters’ first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>We have been searching and searching for the correct nautical term for the act of dumping oil into the water to calm the seas. As a prior USCG vet, I have heard this term but cannot remember it to save my life… Any Ideas?

I did a few quick Google searches, searched a bit of the historical literature and wrote back apologetically,

Thanks for your question, It is a very interesting one. As you probably know we are very intrigued by nautical history. Most of what I know about this practice is referred to as “pouring oil on troubled waters” or some such variant. Ben Franklin actually studied this phenomenon extensively and referred to it as “wave-stilling”. I am unaware of a specific nautical term though. I copied the DSN co-editors in case they might know another term.

I attached 2 documents that are fascinating reads about this if you don’t mind the pdf’s. One is by dutch historian Joost Mertens “The honour of Dutch seamen: Benjamin Franklin’s theory of oil on troubled waters and its epistemological aftermath” and another is a 1884 report by Lieutenant Wyckoff of the US Navy. I plan on reading Franklin’s original paper soon too. Anecdotal evidence but great accounts nonetheless. You have inspired me to write up a post on DSN about this in the near future!

To which he was grateful for the reply.

Ironically we were talking about how devastating it would be to have a hurricane come through the gulf with all the oil sitting there – but then again, perhaps it would ameliorate the hurricane’s effects by limiting evaporation and airborne water spray…

This idea was a little foreign to me, not because it didn’t make sense to me, but because I was thinking of the enormous scale of a hurricane and the much smaller scale of the oil spill (at that time). There would certainly have to be a lot of oil on the water to have any stilling effect. Now in the 63rd day of the spill with no end in sight, lack of scale seems less of an issue.

This idea was a little foreign to me, not because it didn’t make sense to me, but because I was thinking of the enormous scale of a hurricane and the much smaller scale of the oil spill (at that time). There would certainly have to be a lot of oil on the water to have any stilling effect. Now in the 63rd day of the spill with no end in sight, lack of scale seems less of an issue.

The use of oil on troubled waters was discussed by Aristotle and Pliny, both of who described how Mediterranean divers would coat oil around their eyes to “quiet the surface and permit the rays of light to reach them” (Wyckoff 1886). Additionally, fishing vessels and whalers would carry oil, or whale blubber in the latter case, specifically for use in crossing straits known to have rough weather. As Wyckoff wrote in a very interesting historical review of the use of oil in stormy seas:

Whalers have resorted to oil and blubber, in severe storms, for the last two hundred years. Very recently, an old whaler informed me, that it was their custom to hang large pieces of blubber over, each quarter of their vessel, when running before a heavy sea, and it entirely prevented the water coming on board.

Many scientists have recognized the value of local knowledge, which has provided a springboard to many fruitful areas of basic and applied research. Ben Franklin was the first to systemically collect stories and develop hypotheses that he then experimentally tested during his many years in Europe. He captured many instances of folklore by Captains swearing by fish oil in storms, boatswains letting out barrels of blubber to help make landfall in the whitecaps, and seals eating oily fish and producing calm waters around feeding colonies that Scottish sealers used find them. Like all anecdotes, these were met with skepticism. In a letter Franklin published in 1774 from colleagues Rev. Farish to Dr. Brownrigg,

According to his representation, the water, which had been in great agitation before, was instantly calmed, upon pouring in only a very small quantity of oil, and that to so great a distance round the boat as seems a little incredible. I have since had the same accounts from others, but I suspect all of a little exaggeration. PLINY mentions this property of oil as known particularly to the divers, who made use of it in his days, in order to have a more steady light at the bottom. […]

Old PLINY does not usually meet with all the credit I am inclined to think he deserves. I shall be glad to have an authentic account of the Kerwick experiment, and if comes up to the representations that have been made of it, I shall not much hesitate to believe the old Gentleman in another more wonderful phaenomenon, he relates, of stilling a tempest only by throwing up a little vinegar into the air.

Franklin experimentally tested the stilling effects of oil in natural settings, a first at that time, several instances over the course of 18 years. At first, he made fun of Captain’s suggestions of using oil in rough seas, but being the ardent scientist he was, Franklin put these observations to test. He describes his first experiment at a pond in Clapham Commons, where he often stayed:

At length being at Clapham where there is, on the common, a large pond, which I observed to be one day very rough with the wind, I fetched out a cruet of oil, and dropt a little of it on the water. I saw it spread itself with surprising swiftness upon the surface; but the effect of smoothing the waves was not produced; for I had applied it first on the leeward side of the pond, where the waves were largest, and the wind drove my oil back upon the shore. I then went to the windward side, where they began to form; and there the oil, though not more than a tea spoonful, produced an instant calm over a space several yards square, which spread amazingly, and extended itself gradually till it reached the lee side, making all that quarter of the pond, perhaps half an acre, as smooth as a looking-glass.

Subsequent demonstrations were carried out at other ponds in the UK countryside. Franklin hypothesized that oil reduces the friction between air and the surface of the water. Finally, he was able to convince Capt. Bentnick to help him carry out a large-scale experiment in sea-trial conditions off of Portsmouth. With parties stationed at every angle on a windy day to observe the change in sea state, oil from a barge was poured in a tract starting from the Lee-Shore. While the experiment did not temper the swelling of the sea, Franklin and several of the observers noticed very few white-caps and its “surface was not roughened by the Wrinkles or smaller Waves”. Franklin concluded,

… tho’ Oil spread on an agitated Sea, may weaken the Push of the Wind on those Waves whose Surfaces are covered by it, and so by receiving less fresh Impulse, they may gradually subside; yet a considerable Time, or a Distance thro’ which they will take time to move may be necessary to make the Effect sensible on any Shore in a Diminution of the Surff.

What he is saying is when a force causes water to move, the motion does not stop immediately when the force stops. It ripples away and its intensity lessens with time, assuming no new “impulse”. He suggests the oil weakens the effect of the wind, and more quickly lessening the effects of the “impulse”. Franklin contemplates that more time and starting the oil at a greater distance from the windward-shore may produce a larger stilling effect.

Ben Franklin’s experiments did not definitively conclude the hundreds of years of mariner’s anecdotes. Even today it is not clear whether pouring oil on troubled waters produces the desired effect. Also, I might propose that cases where such a measure succeeds are likely to be reported more often so the anecdotes may be biased.

With the impending hurricane season, some have suggested that the oil may calm the waters, giving the Gulf coast States a reprieve. Indeed over 100 years after Franklin’s paper, Lieut. Wyckoff of the United States Navy reported 115 additional reports from the Hydrographic Office, noting all reported successful uses of oil in stormy seas except four. His last report comes from Captain E.L. Arey of the schooner Jennie A. Cheney,

” I used oil with very satisfactory results during the late severe hurricane of the 25th of August, in latitude 31 N., longitude 790 W. The wind having carried away the mainsail, I bent a storm trysail, and continued under that sail until it also blew away. During the time, the vessel was shipping large quantities of water, the sea being very irregular, nearly every one breaking. After the sails were blown away, finding it necessary to do something to save the ship and crew, I took a small canvas bag and turned about five gallons of linseed oil into it, and hung it over the star- board quarter. The wash of the sea caused a little of the oil to leak out, and smoothed the surface, so that for ten hours no water broke aboard. I consider that the oil used, during the last and heaviest part of the hurricane, saved vessel and crew.”

It is difficult to reconcile all the successful reports that operated on the very localized scale of a single ship and the seas around it with the immense scale of the oil-laden northern Gulf of Mexico. Will wave breaks be tempered by the floating oil slick and plume? I took a look at wave height anomaly and sea surface height from satellite data at a couple stations south of Louisiana and did not notice any appreciable difference from April 1 to June 20 greater than background variation. It appeared there was more scatter after the Deepwater Horizon spill compared to the same dates in 2009, but its really all hand-waving.

Unfortunately, this will inevitably be a horrible, but important, experiment and I will be following it intently. The volume of oil out there and rate of spreading is immense. By the time this summer’s storms come around to the upper Louisiana slope, it will only have grown in size. Accurate measure of surface area of the spill and sea state data will be important to test this hypothesis on such a large scale. All these data are being constantly monitored, so it should be apparent relatively quickly after a major storm whether oil does indeed calm troubled waters.

On the other hand, oil has in smaller scale over the course of a long time been spilling into the northern Gulf for decades. These oil rigs surely leak a little here and there, there have been tanker collisions and other major spills, and lest we forget that the Gulf deep seafloor is covered with naturally occurring gas/oil seeps. MacDonald and colleagues followed the path of oil as it left the seafloor into the water column. They found that there was little chemical alteration in the water column, but at the surface slicks formed and the volatile components rapidly evaporated.

This natural seepage has been occurring for centuries, millenia even. Surely any effect of temperament would already be apparent. Additionally, we may not be to detect any difference if oil is always naturally seeping into the Gulf despite major oil catastrophes occurring in the last 50 years, which could mean either not enough volume present to produce an effect or an effect does not exist.

—————————————————————–

Franklin, Benjamin (1774). Of the Stilling of Waves by means of Oil. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 64, 445-460 DOI: 10.1098/rstl.1774.0044

MacDonald, I., Leifer, I., Sassen, R., Stine, P., Mitchell, R., & Guinasso, N. (2002). Transfer of hydrocarbons from natural seeps to the water column and atmosphere Geofluids, 2 (2), 95-107 DOI: 10.1046/j.1468-8123.2002.00023.x

Mertens, Joost (2008). The honour of Dutch seamen: Benjamin Franklin’s theory of oil on troubled waters and its epistemological aftermath. Hosted at BenFranklin300.org

Wyckoff, Lieut. A.B. (1886). The use of oil in storms at sea Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 23 (123), 383-388 (JStor)

The post Pouring Oil on ‘Troubled Waters’ first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>